In the field of metal processing, steel forging is both an ancient and modern forming technique. When discussing the quality of forgings, one technical term frequently appears, forging flow line. For non-professionals, the term may sound somewhat abstract, yet it functions much like the lifeline within the metal, directly determining the service life and mechanical properties of a forged component. This article begins with the fundamental concept and provides a detailed explanation of the formation mechanism, significance, and practical control methods of steel forging flow lines.

Forging flow lines, also known as grain flow or fiber structure, refer to the directional microstructure formed in metallic materials during the forging process. Specifically, when metal is heated and subjected to external forces such as hammering or static pressure, plastic deformation occurs, causing internal impurities and structural features to rearrange along the primary direction of metal flow.

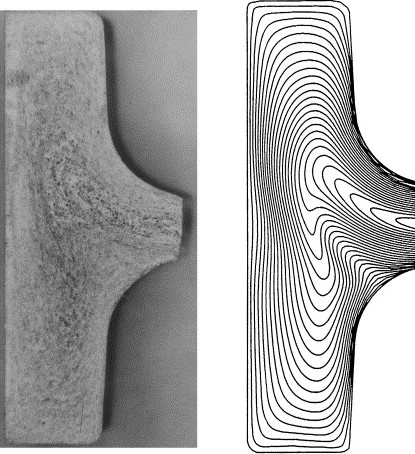

During the smelting process, metals often contain low-melting-point constituents and banded segregation. In subsequent rolling or extrusion processes, these constituents stretch along the deformation direction. Meanwhile, the original grains of the ingot are elongated into strip-like shapes during processing. Even after recrystallization heating restores the elongated grains to equiaxed ones, the streak-like distribution formed by low-melting-point components and banded structures remains. If the longitudinal section of steel is polished and acid-etched, these stripe-like lines become visible to the naked eye; this is the forging flow line.

It is important to clarify that properly distributed forging flow lines are not defects. Almost all metal profiles and components that have undergone rolling, extrusion, or forging exhibit flow lines. They are an inevitable result of plastic deformation and one of the distinguishing characteristics that set forging apart from casting.

The formation of forging flow lines accompanies the entire hot die forging process. When metal is heated between the initial forging temperature and the final forging temperature, the atoms gain sufficient mobility. External forces applied through hammering or static pressure cause plastic deformation, and this deformation process is precisely how forging flow lines develop.

During this process, brittle impurities within the metal are crushed and distributed as granules or chains along the primary elongation direction. At the same time, plastic impurities deform with the metal and form banded distributions along the same direction. As a result, the microstructure of hot-forged metal becomes distinctly directional, creating what is known as forging flow lines.

The forging ratio is an important parameter influencing the degree of flow line formation. Once the forging ratio reaches a certain value, flow lines become clearly defined. At this stage, the mechanical properties of the metal, particularly plasticity and toughness, are significantly higher along the longitudinal direction of the flow lines than in the transverse direction. Therefore, during hot forming, process designers must carefully consider how to achieve a rational distribution of flow lines within the workpiece.

The importance of forging flow lines lies in the anisotropy they introduce. Experimental data show that specimens cut along the fiber direction of steel exhibit higher mechanical properties than those cut perpendicular to it. This means that strength and toughness vary depending on direction.

Take bearing rings as an example. These components have strict requirements for forging flow lines. The flow lines must form concentric circular patterns consistent with the ring’s geometry. Such a distribution effectively improves bearing strength and service life. If the flow lines are improperly arranged, premature failure may occur during operation.

Another example is hammerhead forgings, which must withstand frequent impact loads. Ideally, the forging flow line direction should align with the primary load direction, significantly enhancing impact resistance. Conversely, if the flow line direction is improperly oriented relative to the main stresses, quality issues may arise, potentially leading to fractures during use.

The anisotropy caused by forging flow lines is a common characteristic of deformed metals. To accurately describe flow line distribution, the industry uses clear directional terminology.

In rectangular billets, the length direction is called the longitudinal flow line, the width direction is the long transverse flow line, and the thickness or height direction is the short transverse flow line. For square billets, since width and thickness are equal, the distinction between long and short transverse directions is unnecessary, and both are collectively referred to as transverse flow lines.

In cylindrical or ring-shaped forgings, longitudinal flow lines run along the axial direction, long transverse flow lines follow the tangential, chordal, or circumferential direction, and short transverse flow lines extend radially. Understanding these directional definitions is essential for controlling forging quality.

Mechanical properties typically decrease in the order of longitudinal, long transverse, and short transverse directions. In other words, tensile strength is highest along the flow line direction, lower in the long transverse direction, and lowest in the short transverse direction. This performance variation requires designers to consider the relationship between working stress and flow line direction during the design stage. The basic principle is to align normal working stress with the flow line direction while keeping shear stress perpendicular to it, thereby maximizing load-bearing capacity.

One of the most significant differences between forging and casting lies in the continuity of the metal fiber structure. Forgings produced through precision die forging, cold extrusion, or warm extrusion maintain fiber structures that conform to the component’s geometry, resulting in complete and continuous metal flow lines. This continuity ensures superior mechanical properties and longer service life, advantages that castings cannot easily match.

Generally speaking, castings have lower mechanical properties than forgings made from the same material. During casting, the metal solidifies without undergoing plastic deformation, meaning no flow line structure is formed. Although certain post-processing techniques can improve casting performance, forgings remain the preferred choice for critical components subjected to complex loads.

In practical production, forging flow lines may exhibit various defects. Turbulent flow refers to irregular metal movement that deviates from design expectations. Backflow occurs when metal reverses direction in certain regions, while eddy flow describes areas where metal becomes trapped in cavity corners, resulting in poor movement. All these phenomena represent abnormal flow line distributions.

Major defects, such as turbulent flow, penetrating flow, or chaotic fiber orientation, can significantly reduce mechanical properties. In regions where the flow line direction is perpendicular to the primary stress, stress concentration is likely to occur, creating potential crack initiation sites and compromising operational safety.

Such defects are typically associated with factors including die design, forging temperature, deformation speed, and lubrication conditions. For instance, an improperly designed die cavity may create uneven resistance to metal flow; excessively low forging temperatures reduce metal fluidity; and overly rapid deformation can cause localized overload.

Inspection of forging flow lines is an essential method for ensuring forging quality. By examining flow line distribution, manufacturers can verify whether components meet technical specifications and design requirements. A commonly used technique is macro-etch testing: samples are taken from the longitudinal section, polished, and acid-etched so that flow line patterns can be observed with the naked eye or under low magnification.

Inspection results not only provide a basis for quality evaluation but also guide process improvements. Based on observed distributions, technicians can adjust forging parameters, such as changing the forging direction, optimizing billet geometry, or modifying temperature and deformation levels, to enhance fiber structure and overall performance.

In failure analysis, flow line inspection helps identify root causes. When a component fractures during service, analyzing the flow lines near the fracture surface can reveal whether defects were present and how they contributed to the failure mode, providing scientific support for process optimization.

Optimizing flow line distribution begins with sound process design. First, the preform shape should be carefully designed to promote uniform and orderly metal flow within the die cavity. Second, selecting an appropriate forging ratio is essential to ensure that flow lines are fully developed and properly distributed. If the forging ratio is too small, flow lines may be indistinct and anisotropy insufficient; if too large, the flow lines may become excessively dense, increasing deformation resistance.

Die design is another critical factor. Fillet radii, draft angles, and flash groove configurations all influence metal movement. A well-designed die structure reduces dead zones and prevents backflow or eddy formation. Additionally, advanced techniques such as multi-directional forging and isothermal forging enable better control of metal flow direction and help achieve ideal flow line patterns.

Lubrication conditions should not be overlooked. Effective lubrication reduces frictional resistance, allowing smoother metal flow. However, lubricants must be compatible with deformation temperatures to avoid decomposition and adverse effects at high temperatures.

The automotive industry is one of the largest users of forged components. Engine crankshafts, connecting rods, transmission gears, and shaft components all require strict control of forging flow lines. For example, the flow line distribution in both the big end and small end of a connecting rod directly affects fatigue strength. A combined roll-forging and die-forging process can ensure continuous flow lines along the rod’s contour, significantly extending service life.

The aerospace sector imposes even stricter requirements on forging quality. Aircraft landing gear and engine disk shafts often endure alternating and impact loads. Precise control of forging flow lines ensures optimal mechanical properties in critical regions. Some key forgings even require individual flow line inspection to guarantee full compliance.

The tool manufacturing industry also places great emphasis on flow line control. In addition to hammerheads, various dies and cutting tools must consider fiber orientation. Proper flow line distribution enhances wear resistance and resistance to chipping, reducing the risk of failure during operation.

Forging flow lines are one of the core indicators of hot die forging quality. They reflect the metal’s flow behavior during forming and directly determine mechanical performance and operational safety. Understanding their formation mechanism and directional characteristics is crucial for designers, process engineers, and quality inspectors alike. In practical production, manufacturers should leverage the higher longitudinal strength provided by fiber structures through rational process design, ensuring that flow lines remain continuous and aligned with load directions. At the same time, a comprehensive inspection system should be established to detect defects such as turbulent flow or backflow and to continuously refine process parameters. For end users, a basic understanding of forging flow lines supports informed decisions during material selection and acceptance, helping ensure that components meet performance requirements.